Introduction

While regional universities are traditionally strong at attracting diverse students, one of the major challenges they face is attrition, which continues to be high in comparison with state and national averages. Since its establishment in 1984, a number of changes has occurred in the Academic Learning Centre (ALC) which has enabled staff to keep abreast of the needs of the changing student population at CQUniversity. However, there are still shortcomings in the style of learning support offered. Although the numbers of students seeking assistance have increased Academic Learning Advisors (ALAs) are acutely aware of the repetition in the advice given and the low numbers of students attending workshops. There are however, increased numbers of students looking for assistance a few days before the assignment due date and these assignments show a lack of preparedness for university study. Accepting and understanding the diversity and behaviours of CQUniversity students has resulted in a review of services and the development of a set of goals that staff felt would guide the ALC to continue to improve service and reputation. The embedded approach to providing academic advice outlined in this case study is in the early stages of implementation and continues to grow and change in order to develop a service that suits diverse student cohorts. Its purpose is to add another layer of support that assists all students with academic literacy skills instead of only those who proactively or reactively seek help.

Context

The Academic Learning Centre (ALC) is one of two arms of the Academic Learning Services Unit (ALSU). The second arm of the ALSU is Skills for Tertiary Education Preparatory Studies (STEPS), an enabling program that provides a pathway for people wishing to gain entry to and excel in higher education. The ALC has grown to offer a number of on-campus and online services in four discipline areas: Academic Communication, Maths and Statistics, Computing, and Science. Due to increasing demand and a desire to increase student independence, a range of learning and teaching strategies has been implemented and improved strategies for engaging distance students utilised. An increase in online services has required a change in the way ALAs view their role, and professional development has been undertaken by all staff interested in online support and resource development. Greater interest from other support staff and academics has assisted in raising the ALC profile and an interest in the approaches this unit is taking to assist with attrition.

ALC staff members have known for some time that the add-on style of assistance and provision of workshops is insufficient for a number of reasons. Firstly, as the ALC’s promotion platform and reputation have grown, an increasing number of students is self-nominating for one-on-one support through face-to-face consultations, or submitting online for review, and in peak periods staff struggle to manage the load. During these consultations, ALAs give feedback on similar academic skills, resulting in repetitive teaching but highlighting students’ lack of preparedness for university literacy tasks. The requests for support are frequently one off visits rather than one in a series that would enable a student time to develop skills. Wingate (2006) argues that academic literacy support as a reactive or deficit approach is an ineffective way to enhance student learning. Although ALC promotion focuses on educating students about what support is available and espouses the value of the assistance to their success at university, asking for this assistance requires students’ to take risks and practice behaviours that are unfamiliar to them or may make them uncomfortable (Lawrence, 2005). These behaviours are related to the development of socio-cultural competencies, specifically help and information seeking behaviours, and attitudes about seeking feedback (Lawrence, 2005). These socio-cultural competencies are necessary for a successful transition to university; however, they may take some time and scaffolding to develop (Lawrence, 2005; Wilson, 2012). As a result, many students who should seek assistance in their first year do not choose to attend; they may be embarrassed or afraid to ask, and some see it as an admission of failure (Bloy, Buckingham & Pillai 2006). Although the ALC provides many adjunct workshops both on campus and in online sessions, and encourages students to interact with ALAs, another blocker to seeking assistance identified by Chanock (2007) is that these are largely generic, servicing students from many disciplines, and as such are often regarded as remedial. Kift (2009) also contends that many students do not attend these add-on services due to varying life factors, or competing demands. As a result, there are still many students who view the ALC services as a quick fix or do not seek assistance, and some only do so when they fail.

It is clear that a far more proactive approach is needed than has been adopted in the past; one that meets the needs of an increasingly diverse university student population. This includes not only international students but also domestic students who have a non-English speaking background. It also includes: those who are underprepared for university education and who have not undertaken STEPS; students who have the capacity to achieve higher education success but, due to a long absence from study, lack confidence; “first-in family” students who have no family tradition in higher education; students with disabilities; distance students or those studying by flexible modes; and mature-aged students who may be on a determined quest for high distinctions. “With widening participation across tertiary education and the increasing numbers of international students, it can no longer be assumed that students enter their university study with the level of academic language proficiency required to participate effectively in their studies” (Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations [DEEWR], 2008, p.1). Understanding student diversity and identifying the risks that they face, enables the ALC to provide appropriate scaffolding of learning to increase their independence and success.

An embedded approach to providing student support

A body of knowledge has emerged in the last 20 years, which focusses on the embedding of academic literacy skills into university programs, as well as demonstrating agreement on the benefits of such initiatives. The benefits have been documented via a meta-analysis of 51 studies by Hattie, Biggs, and Purdie (1996) as well as in research by Tinto and Pusser (2006). Furthermore, DEEWR (2008) outlines 10 good practice principles for English language proficiency in academic studies for international students, and suggests that examples of good practice demonstrate integration of these skills. Additionally, foundation literacy skills can increase potential for the success of students transitioning to university and can also bridge the gap for students from diverse backgrounds (Black & Rechter 2013; Cuseo, 2003). The DEEWR steering committee was guided by a number of other key ideas, as illustrated by the following quote from the report: “Development of academic language and learning is more likely to occur when it is linked to need (e.g. academic activities, assessment tasks)” (2008, p. 2). Additionally, Tinto (2009, p. 9) sees linked units as a way to “provide a coherent, shared learning experience that is tailored to the needs of the students”. The positive views of this approach indicate that it should be incorporated into learning centre strategies to support students.

It is clear that there are many advantages of an embedded approach. Firstly, it enriches student learning and provides a supported learning environment that, in particular, links to several of the scales identified by the Australian Survey of Student Engagement (ACER, 2009). Additionally, this approach does not target a particular group of students and so normalises the focussed approach to learning about academic literacies (McWilliams & Allan 2014). Black & Rechter (2013) and Murray (2013) propose a transitioning program and suggest that improved English Language Proficiency levels are necessary for all students, irrespective of Socio Economic Status or non-English speaking backgrounds (NESB). These approaches assist in creating a multi-layered approach which is designed to benefit all students with the development of fundamental skills and confidence, while continuing to offer individual services. Furthermore, the embedded approach focuses on assessment as a point of integration and engagement, provides specific learning opportunities and links to a model that aids transition to university (Taylor, 2008). DEEWR (2008, p. 2) states that “development of academic language and learning is more likely to occur when it is linked to need (e.g. academic activities and assessment tasks)”. Benefits of collaboration between ALAs and academics around assessment will be valued by students if they contribute a small percentage to the final grade (Taylor, 2008). In this model, assessments link both to the learning centre teaching and to the discipline as they allow feedback to be given on course content and writing processes. Furthermore, Brooman-Jones, Cunningham, Hanna & Wilson (2011) describe a model of academic literacy support that is embedded through assessment where discipline and academic literacy assignments connect outcomes from both. As a result of the benefits outlined, many learning centres have refocussed their mission statement to one that involves creating engaging learning environments that include collaborations between discipline-specific academics and academic advisers.

To implement this approach it is necessary to develop partnerships between academic and support staff. Dudley-Evans (2001) describes collaborative and team teaching approaches as those that involve working together to provide benefits for the student, learning centre and faculty staff. However, initiatives featuring a range of collaborative approaches are documented. Some studies debate the pedagogy that could be used and others attempt to identify best practice models (McWilliams & Allan, 2014; Dudley-Evans, 2001; Brooman-Jones, Cunningham, Hanna & Wilson, 2011); however, several authors indicate that if it is to be successful, a flexible approach is needed: one that is a fit for the students and context where it will operate. Others positively evaluate collaborations that have adopted a holistic approach to university transition and retention (Einfalt & Turley, 2013; Kift et al., 2010). These initiatives support the view that the responsibility of providing support is not an individual faculty or department concern, rather whole of institution. This view aligns with CQUniversity’s Retention Plan titled: It’s everyone’s business (2014).

Impacts of students’ backgrounds and behaviours

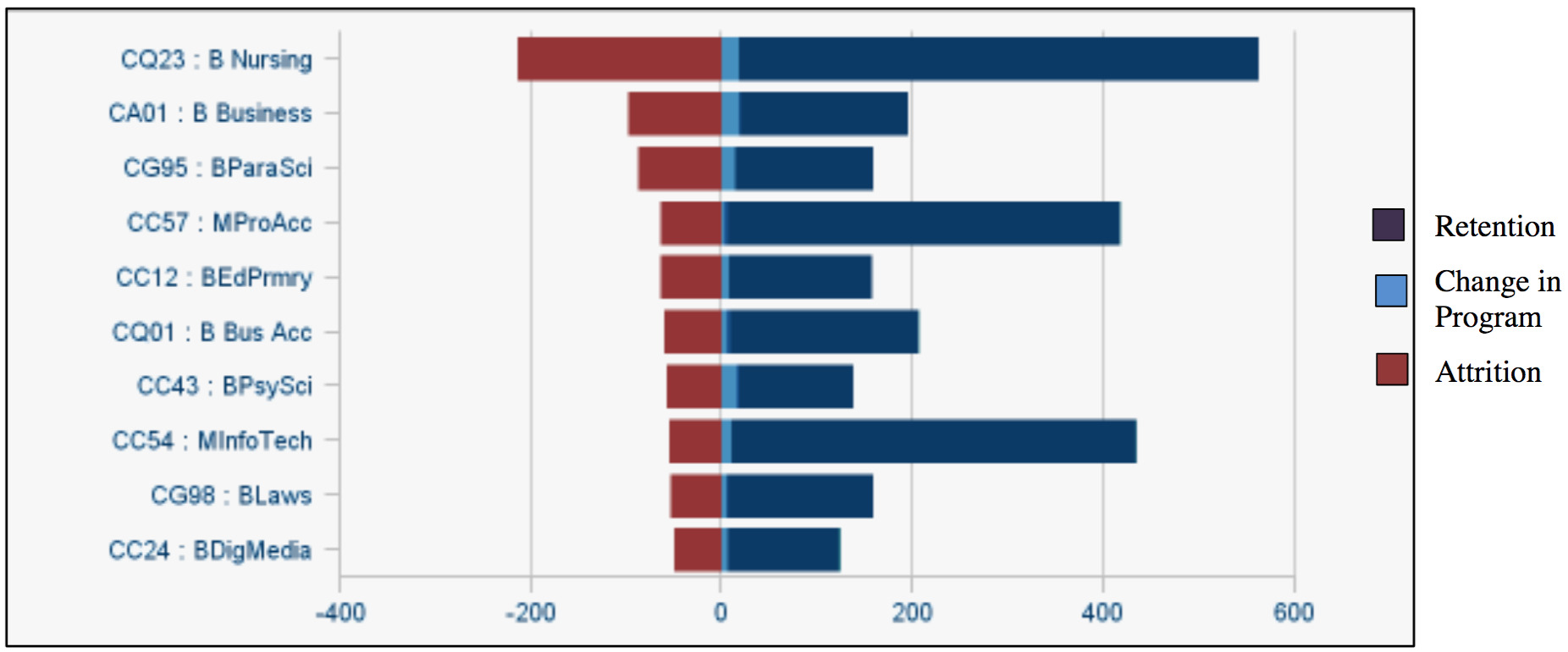

Students’ diverse backgrounds and behaviours must be examined and their needs considered in any new approach. One of the first cohorts targeted for an embedded approach was the undergraduate nursing cohort. Their need for extra support with academic literacy skills had been evident in the high levels of support sought from the ALC over the previous few years. The Bachelor of Nursing program has the highest intake of all undergraduate students from a single program at CQUniversity, as well as the highest level of attrition from any one program (see Figure 1 below); as such, this is a vulnerable group. The vast majority of CQUniversity Bachelor of Nursing students are non-traditional students, with 81% being mature-aged in Term 1 of 2015 and 83% in Term 2 (CQUniversity, 2015). These students are likely to have responsibilities such as work and family that compete with their study. The University of Western Sydney - Mature Age Student Equity Project 2009 -2011 (De Silva, Robinson & Watts, 2011) showed that students with varied time commitments may seek ‘quick-fix’ solutions rather than developing skills for lifelong learning. It also showed that 30.5% of students surveyed, were unaware of the range of services available to support them. ALC usage figures confirm this trend of quick-fix behaviour from Bachelor of Nursing students, as evidenced by the high level of online submissions in comparison with attendance at Blackboard Collaborate sessions. Additionally there are still many who do not access services promoted by email, via Moodle (the learning management system) or during residential schools and orientations.

Another factor that may impact on the success of this group is the mode of entry into the Bachelor of Nursing degree. According to the Queensland Tertiary Admissions Centre (QTAC, 2015), the entry figures for a Bachelor of Nursing undergraduate degree range from Overall Position (OP): 7, Selection Rank (SR): 88, Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR): 86.67 to OP 19, SR: 60, ATAR: 49.95 with a significant number of universities opting for OP: 15, SR: 66, ATAR 62.25. The current prerequisite for entering the Bachelor of Nursing degree at CQUniversity is at the lower end of the range: an OP: 17, SR: 63, ATAR: 56.55, with no prerequisite for English or Maths. Moreover, Norton (2014, p. 3) warns that there appears to be a correlation between the number of students who struggle academically and the easing of entry requirements. In addition, there has been a significant increase in the number of students making the transition from Vocational and Educational Training (VET) to higher education qualifications (CQUniversity, 2015). Research has found that those transitioning from VET to higher education are likely to face many and varied challenges (Watson, 2008; Watson, Hagel & Chester, 2013; White, 2014). Urban et al. (1999, cited in Watson, 2008) suggest that the method of entry to university has been shown to affect students’ completion rates. Endorsed Enrolled Nurses (EENs) who transition to university after studying at TAFE are often given credit for most first year Bachelor of Nursing courses. Yet they may be disadvantaged by academic elements affecting VET transition to undergraduate study which include:

- Understanding of the task and preparation of the task (White 2014)

- Academic literacy (writing arguments, self-reflection, critical thinking and analysis) (Catterall & Davis 2012)

- Expectations around referencing and information literacy skills (White 2014)

- Academic numeracy (Catterall & Davis 2012).

- Putting highly context specific content and theory into practice (Watson 2008).

The comprehensive embedded model being undertaken by the ALC will make such a pathway more accessible for students such as these in the future and enable success.

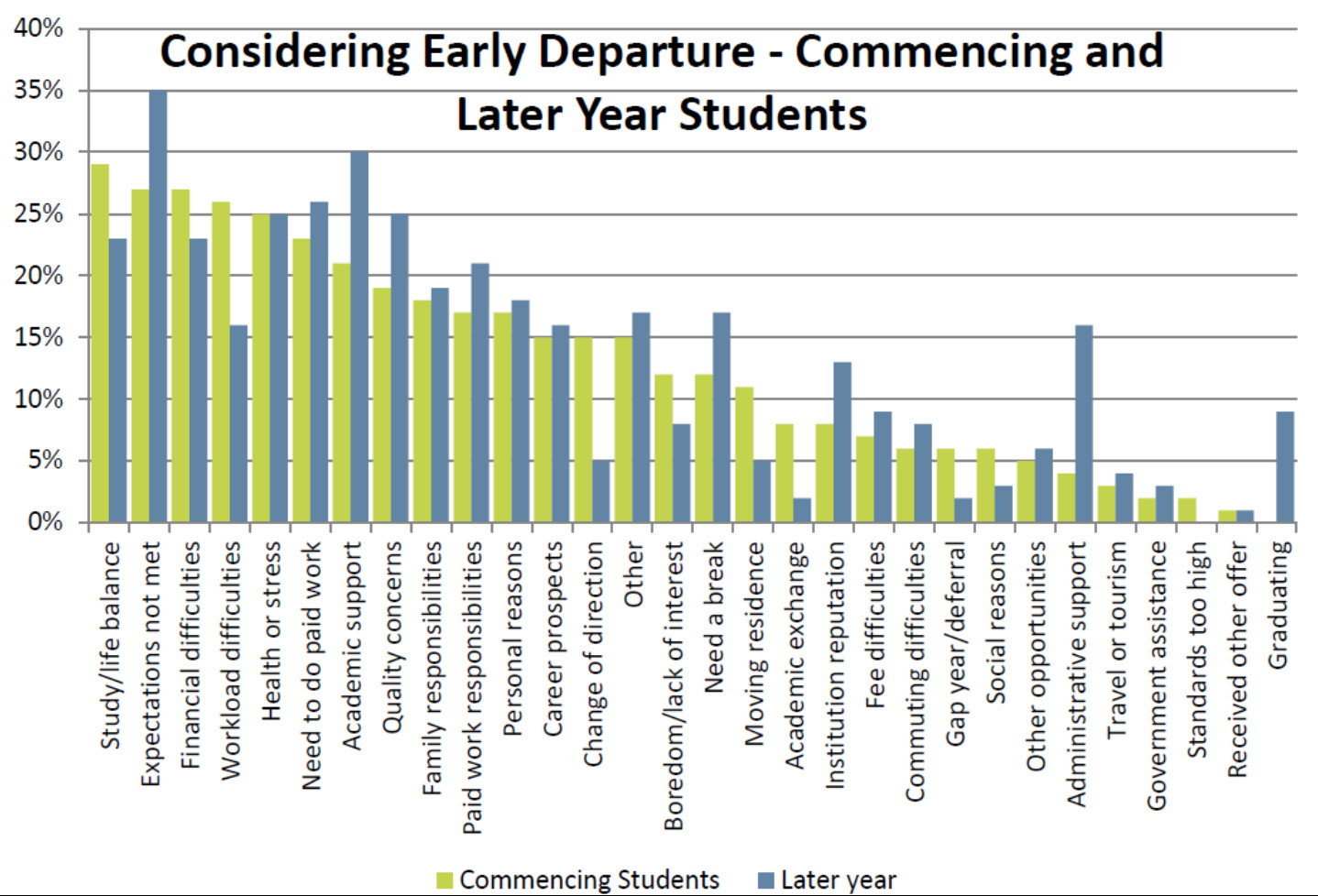

It is evident in the pass rates of non-traditional students that factors that may put students at risk can be overcome by the adoption of productive approaches to learning and support in their first year (Bradley et al., 2008; Lizzio & Wilson, 2010). Investing time in attending lectures and tutorials, and/or engaging with the online environment, developing a social network of peers, seeking help where needed and achieving an appropriate work-life-study balance can all be crucial for students to succeed (Wilson, 2012). These behaviours are reflected in the “five senses of success” identified by Lizzio (2006) namely, felt levels of connection, capability, purpose, resourcefulness and their sense of academic culture. These factors are represented as some of the 30 reasons that students were considering an early departure (Figure 2) in the 2013 University Experience Survey (cited in CQUniversity, 2014). This survey identified the most common reason cited by first year students was study/life balance, while later-year students identified that their expectations were not met. However, of concern for the ALC is the high proportion of students who cited lack of academic support as a key reason for leaving (See Figure 2). Promotion of ALC services is occurring in a range of forums but still many students did not access the centre. Providing support in an embedded way could improve this factor and reduce the need for promotion of the service.

Learning by distance mode is also recognised by some studies as a factor contributing to failure of students and attrition. In 2015, there were 64,342 undergraduate enrolments at one of eight campuses at CQUniversity, or enrolled as distance education, or a combination of both. Approximately 50% of these students chose a distance enrolment in terms one and two and approximately 60% chose distance in term three (CQUniversity, 2016), which traditionally has more distance offerings. Furthermore, in 2015 a vast majority of CQUniversity Bachelor of Nursing students elected to complete their degree via distance mode: 73% in Term 1; 88% in Term 2; and 100% in Term 3; hence, another possible risk factor for this group. In fact, in 2014 the rate of attrition amongst distance students was 10% higher than that of on-campus students (CQUniversity, 2015). Surprisingly however, in the previous five years there was also a higher rate of withdrawals and absent fails (none or insufficient assessment items completed) in the nursing cohort. Current ALC approaches to assistance with academic literacy skills are cognisant of these patterns and inclusive of distance students, providing a range of modes of access for students, and it is evident in the number of consultations that this group accesses this support, yet many do not use these adjunct services.

There are other programs recognised by the ALC that have similar diversity in their cohorts as the nursing students, similar patterns of access, and which may also be at risk. One of these is the Bachelor of Business cohort. This is a smaller group but the attrition in this group is high (see Figure 1). This group can also enter by VET pathways and as mature age students with credits for experience in the business field. They are also school leavers entering with low OP scores. Additionally, programs where high numbers of international NESB students are enrolled, such as Information Technology degrees (masters and undergraduate), come to the attention of the ALC, as these students tend to be high users of individual services for English Language assistance; these programs also have high numbers of academic misconduct penalties. In 2015, there was a 34% rate of attrition from the Bachelor of Information Technology degree. While, in contrast, the Masters of Information Technology has a low attrition rate, yet large numbers of international students enrolled in this program are given academic penalties for plagiarism each term. Such issues can result from low literacy proficiency and a lack of understanding and knowledge of the requirements for referencing or Australian university culture in general (Bretag, 2005; Devlin & Gray 2007; Wearring et al., 2015). However, there is evidence that plagiarism can be significantly reduced if students receive adequate training in academic literacies (Bretag, 2005); hence, it is important for the ALC to adopt more effective ways of addressing the academic needs of these diverse groups of students.

The model adopted

In an attempt to reduce the high intensity and quick-fix approach to advising, and encourage students to see help-seeking as normal behaviour the ALC has added embedded modules of academic literacy skills to their repertoire of services. This also makes better use of resources, while supporting student success and reducing academic risk. In developing an appropriate model, it was important to not simply replicate other models outlined in case studies, as the vast diversity and numbers of distance students at CQUniversity required a much more flexible and multi modal approach. These modules are designed around fundamental skills but linked closely to the assessment task of the courses in which they are embedded. The model adopted is such that academic literacy teaching is embedded into four core discipline courses at CQUniversity, utilising four to six hours of tutorial time. The amount of time given for Academic Literacy module, the choice of delivery weeks and modes vary, depending on the academic staff, the course, the cohort, and the due date of the task. Dudley-Evans (2001) describes the most effective approach of academic literacy support as one that is embedded in the discipline subject, so that discipline and academic literacy staff co-teach in the same space. Therefore, in the ALC model when classes are internal, discipline and academic literacy staff co-teach in the same space on campus. The focus is on the generic structure and features of the first assessment piece, as well as on analytical thinking, referencing and writing skills. This model provides an opportunity for greater collaborative support, founded on a juncture of goals to provide for the needs of the diverse student cohort.

The Academic Literacy Skills project is funded by the ALSU, but there has been participation through several strands. The initial modules were developed when funding was provided by one Dean of Teaching and Learning to employ a staff member to work closely with the ALC during the development of the embedded component for one of his school’s core courses. This was vital to ensuring the modules were relevant and linked to the core course chosen as a pilot. Wingate (2006) points out that academic literacy cannot be separated from discipline/subject content and a built-in or embedded approach where learning is developed through the discipline teaching should be adopted. During development of subsequent embedded modules, collaboration occurred between ALC staff and course coordinators via phone, video conference, or on one of the ten campuses where ALC advisers are employed. Thirty four academic lecturers were involved in the courses; many liaised only with staff on the campus where internal teaching occurred. These collaborations enable ALAs to gain deeper knowledge of the coordinators concerns and goals, as well as lead a backward-mapping process to determine the academic skills that students require to be successful in the assessment task. Academics assist by providing models of assessment tasks, insight into student needs and ensure that outcomes and learning resources are suitable. These collaborations also ensure that the modules and resources align to the assessment and that appropriate scaffolding is provided. As staff and situations vary the level of collaboration on the assessment tasks, modules and resources also varies.

Another key in this collaboration and in delivery are other support services. Librarians provide research skills online and linked to the ALC designed Moodle site, and counsellors deliver time management and stress management techniques to internal students through face to face and video conferencing modes. Although this project has been predominantly led by the Academic Communication discipline area of the ALC, the computing team has a role in providing resources to assist students with formatting essays, reference lists and assignments that are visual texts such as brochures.

As a result of the range of teaching modes and spread of the staff across numerous locations, technology is a key to ensuring the smooth delivery of the modules. Therefore, the process of collaboration between ALC staff who assist with resource development, on campus commitments, or provide on line support via Blackboard Collaborate is done via jabber and video conferencing. This situation is unlike other case studies where students are taught these skills internally. At CQUniversity a variety of modes for implementation of the modules is necessary as students enrol in these courses both internally or distance. As a result, in some situations the delivery of academic skills becomes the sole role of the ALC. The breakdown of distance and internal students is almost equal (see Table 1); consequently, a Moodle site was developed for each of the courses by the ALC. Here learning is sequenced, and learning experiences are provided through a selection of audio visual materials. Furthermore, the ALC has developed a series of Info Sheets with accompanying activity sheets and recordings. Additionally, online quizzes provide opportunities for students to self-assess on topics and answer sheets are provided to check skill development. Other resources are developed for the online and on campus environments including power points and learning activities. These are developed initially for classroom delivery and later adapted for online use through Blackboard Collaborate, ensuring that the collaboratively determined outcomes stay the focus no matter how the modules are delivered. These provide opportunity for internal students to review content and skills in their own time using. Additionally, students are provided with a timetable of Blackboard Collaborate workshops organised by the ALC which enables them to have an interactive experience while developing the skills required. Alternatively, both distance and internal students can access ALC staff on a campus near them for face- to- face interactive sessions, advertised as workshops linked to their course, instead of joining via a virtual room. Academics promote these many modes of delivery showing the value of them to the students and explaining their links to the assessment task.

Benefits to students engaged in the project are evident already. Although there are some students who have not accessed the material, the improved quality of tasks submitted to lecturers has been noted and feedback from students seen in forum posts indicates the value of the method of support. Academic staff have also been very grateful for the modules and praised the quality of the material and the comprehensiveness of the Moodle sites Furthermore, improvements in assessment tasks occurred, moving towards providing formative assessment tasks in first year subjects that allow students to develop their academic literacy skills. Additionally, as ALC staff examined the assessment tasks to carry out back mapping and identify possible obstacles for students, conversations took place and some academics began to adjust assessment tasks to ensure students success with them.

As well as benefits for students, there have been some unexpected benefits related to professional development and skill development for ALC staff. Prior to this project ALAs had limited skills with some of the technology, and as a result training and confidence building have been required. This was provided by specialist staff to small groups of ALAs online and via Collaborate. Additionally, a number of team leaders has emerged and these staff now have course coordinator roles within the ALC. Tasks such as scheduling workshops, on campus and Blackboard Collaborates has become part of their role, along with curriculum development and liaising with academics. ALAs are supported by the Head of Services and an administration officer. Another benefit has been the raising of our reputation within the university as a unit that has a range of skills and backgrounds. Additionally, this project has also provided practical strategies and resources to assist academic staff to utilise skills they learn in other class groups. It is evident that many lecturers did not have the confidence and skills to deliver the initiative themselves but it is envisaged that their observations of ALAs, and the resources provided will assist them to deliver this in other courses. A positive outcome can be achieved from the sharing of expertise which results in capacity building amongst staff involved (Hillege, Catterall, Beale, Stewart 2014), and ALAs are only just starting to see the possibilities this approach brings.

The future

Curriculum is a dynamic process and in curriculum development there are always changes that occur that are intended to improve. These changes are occurring in the project described above, and as the ALC moves into the third iteration of some of the modules, and new courses are added to the project, comments from staff and students who have engaged in the material are used to inform future sites resources and activities. The formal evaluation of the project will enable the ALC to adjust the approach and promote it to other discipline staff, as well as garner support for such changes in proactive teaching of fundamental skills.

The size of the project has grown quickly and the organisation of it has become a complex task but benefits are already evident. The ALC hopes to encourage staff to consider collaborating as a broader team to embed these skills into other core courses using a carefully planned and meaningful approach. Additionally, sustainability is expected as evidenced in the follow up results of studies from a range of universities and involving a range of different cohorts. These indicate that students were able to transfer the knowledge they had gained to other courses. This success also has “a flow on effect in the development of motivation and self-empowerment” (Hillege et al., 2014, p.690). This approach can also extend to embedding more computing as well as maths, statistics, science fundamental skills into core courses. Finally, greater connections to course assessments would be a valuable change, as early assessments in embedded academic literacy units will be valued by the student if they contribute a small percentage to the final grade making them both summative and formative (Taylor, 2008). Such tasks will also allow the staff to identify students who are at risk or lacking confidence.

A collaborative support model is the long term goal of the ALC yet there is a still a disconnection between academics in schools, advisers and support staff in a range of areas, all working in silos but with a similar purpose. The recently adopted retention statement indicates that providing support should not be the responsibility of an individual unit. Other authors concur, stating that members from all services attempting to support students need to move beyond the separateness of academic, administrative and support services and create a whole of institution system (Kift et al., 2010; McInnis, 2003). This initiative of embedding Academic Literacy Skills into courses provides an opportunity to trial a model, evaluate its effectiveness and identify the best approach for adverse group of students to develop academic literacy skills. It is an essential contribution to a comprehensive, integrated, coordinated and collaborative strategy that will assist with “improving the student learning experience in order to boost retention, progress and ultimately, competition rates” (DEEWR, 2009, p.15).The ALC’s belief is that embedding academic literacy skills into discipline courses through collaboration with lecturers and library staff will assist all students to improve their writing, and should increase students’ confidence in approaching their study as well as encourage them to see ‘help seeking’ as a useful addition to the solution. The ALC has confidence that staff at CQUniversity can develop a common goal in providing greater thinking, research, referencing and writing skills for the diverse student group.

The authors may be contacted via:

Valerie Cleary

v.cleary@cqu.edu.au

References

Black, M., & Rechter, S. (2013). A critical reflection on the use of an embedded academic literacy program for teaching sociology. Journal of Sociology, 49(4). 456-470, doi: 10.1177/1440783313504056

Bloy, S., Buckingham, L., & Pillai, M. (2006). Using a developmental approach to enhance students’ learning: A model of learning support for both traditional and non-traditional learners. De Montfort University Open Research Archive

Bradley, D., Noonan, P., Nugent, H. & Scales, B. (2008). Review of Australian Higher Education: Final Report. Canberra: Australian Government.

Bretag, T. (2005). Implementing plagiarism policy in the internationalised university. (Doctoral dissertation). University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA.

Brooman-Jones, S., Cunningham, G., Hanna, L., & Wilson, D. N. (2011). Embedding academic literacy – A case study in Business at UTS. Journal of Academic Language & Learning, 5(2), A1-A13, Retrieved from http://journal.aall.org.au

Catterall, J. & Davis, J. (2012). Enhancing the student experience: transition from vocational education and training to higher education Retrieved from http://voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A51911

Chanock, K. (2007). What academic language and learning advisers bring to the scholarship of teaching and learning: Problems and possibilities for dialogue with the disciplines. Higher Education Research & Development, 26(3), 269-280. doi: 10.1080/07294360701494294

CQUniversity (2014). CQUniversity Retention Plan 2014 – 2019: It’s Everybody’s Business Retrieved 24 October 2016 http://policy.cqu.edu.au/Policy/policy_file.do?policyid=2949

CQUniversity (2016). Academic Dashboard, Attrition & Retention (1st Year): Dashboard, Program Performance. Retrieved 24 October 2016 https://radar.cqu.edu.au/ibmcognos/cgi-bin/cognosisapi.dll

Cuseo, J. (2003). The “big picture”: Key causes of student attrition and key components of a comprehensive student retention plan. Marymount College: CA.

Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) (2009). Good practice principles for English language proficiency for international students in Australian universities. Retrieved from http://www.web.uwa.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/451327/GPG_AUQA_English_language_proficiency_for_International_Students.pdf

De Silva, S. I., Robinson, K. & Watts, C. (2011). The University of Western Sydney - Mature Age Student Equity Project 2009 -2011. Retrieved from http://www.westernsydney.edu.au/\\_data/assets/pdf\\_file/0005/391361/MASEPFinalReport121012.pdf

Devlin, M., & Gray, K. (2007). In their own words: A qualitative study of the reasons Australian university students plagiarize. Higher Education Research and Development, 26(2), 181-198. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cher20

Dudley-Evans, T. (2001). Team teaching in EAP: Changes and adaptations in the Birmingham approach. In J. Flowerdew & M. Peacock (Eds), (2001). Research perspectives on English for academic purposes. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Einfalt, J. & Turley, J., (2013). Partnerships for success: A collaborative support model to enhance the first year student experience, International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education 4(1), 73-84, doi: 10.5204/intjfyhe.v4i1.153.

Hattie, J., Biggs, J. & Purdie, N. (1996). Effects of learning skills interventions on student learning: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 66(2), 99-136. Retrieved from http://www.learningandthinking.co.uk/Effect of Learning Skills.pdf

Hillege, S. P., Catterall, J., Beale, B. L., & Stewart, L. (2014). Discipline matters: Embedding academic literacies into an undergraduate nursing program. Nurse Education in Practice 14(6), 686-691. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2014.09.005.

Hocking, D. & Field house, W. (2011). Implementing academic literacies in practice. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 46(1), 35-47.

Kift, S. (2009). Articulating a transition pedagogy to scaffold and to enhance the first year student learning experience in Australian higher education: Final Report for ALTC Senior Fellowship Program. Retrieved from http://fyhe.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Kift-Sally-ALTC-Senior-Fellowship-Report-Sep-092.pdf

Kift, S., Nelson, K. & Clarke, J. (2010). Transition Pedagogy: A third generation approach to FYE – A case study of policy and practice for the higher education sector. The International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education,1(1), 1-20.

Krause, K.; Hartley, R.; James, R. & McInnis, C. (2005). The first year experience in Australian universities: Findings from a decade of national studies. DEST, Canberra. Retrieved from http://www.dest.gov.au/sectors/higher_education/publications_resources/profiles/first_year_experience.htm

Lawrence, J. (2005). Re-conceptualising attrition and retention: integrating theoretical, research and student perspectives. Studies in Learning, Evaluation, 2(3), 16-33. Retrieved from https://eprints.usq.edu.au/839/1/Lawrence\\_SLEID-2005-85.pdf

Lizzio, A. (2006). Five senses of success: Designing effective orientation and engagement processes. Unpublished manuscript, Griffith University.

Lizzio, A., & Wilson, K. (2010. November 18-19). Assessment in first-year: beliefs, practices and systems. Paper presented at ATN National Assessment Conference, Sydney, Australia. Retrieved from https://www.griffith.edu.au/\\_\\_data/assets/word\\_doc/0005/525344/11-Lizzio-and-Wilson-First-Year-Students-Appraisal-of-Assessment-paper.docx

McInnis, C. (2003). Touchstones for excellence: assessing institutional integrity in diverse settings and systems. In E. De Corte (Ed.), Excellence in higher education. London: Portland Press

McWilliams, R., & Allan, Q. (2014). Embedding academic literacy skills: Towards a best practice model. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 11(3), 1-20. Retrieved from http://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp

Murray, N. (2013) Widening participation and English language proficiency: a convergence with implications for assessment practices in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 38(2), 299-311. Retrieved from http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/50607

Queensland Tertiary Admissions Centre (QTAC). (2015). Courses & institutions: Nursing. Retrieved from http://www.qtac.edu.au/

Taylor, J. (2008). Assessment in first year university: A model to manage transition. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 5 (1). Retrieved from http://jutlp.uow.edu.au

Tinto, V. & Pusser, B. (2006). Moving from theory to action: Building a model of institutional action for student success, National Postsecondary Education Cooperative, Department of Education, Washington, D.C.

Tinto, V. (2009). Taking student retention seriously: Rethinking the first year of university. Keynote speech: ALTC FYE Curriculum Design Symposium, QUT: Brisbane, Qld. Retrieved from http://www.fyecd2009.qut.edu.au/resources/SPE_VincentTinto_5Feb09.pdf

Turner, J. (2004). Language as Academic Purpose. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 3(2), 95-109.

Veitch, S., Johnson, S., & Mansfield, C. (2016). Collaborating to embed the teaching and assessment of literacy in Education: A targeted unit approach. Journal of Academic Language & Learning, 10(2), A1-A10. Retrieved from http://journal.aall.org.au

Watson, L. (2008). Improving the experience of TAFE award holders in higher education’, International Journal of Training Research. 6(2), 40-53. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com

Watson, L., Hagel, P. & & Chesters, J. (2013). A half open door: pathways for VT award holders into Australian universities. NCVER. Retrieved from https://www.ncver.edu.au/\\_\\_data/assets/file/0013/7321/half-open-door-2659.pdf

Wearring, A., Le, H., Wilson, R. & Arambewela, R. (2015). The international student’s experience: An exploratory study of students from Vietnam. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 14(1), 71-89. http://iejcomparative.org

White, S. (2014). Transitioning from vocational education and training to university: strengthening information literacy through collaboration, Retrieved from https://www.ncver.edu.au/publications/publications/all-publications/transitioning-from-vocational-education-and-training-to-university-strengthening-information-literacy-through-collaboration

Wilson, K. (2012). Engaging Commencing Students who are at risk of academic failure: Frameworks and Strategies. The International First Year in Higher Education Conference New Horizons Sofitel Brisbane 26-29 June https://www.griffith.edu.au/\\_\\_data/assets/powerpoint\\_doc/0016/525220/4-Students-At-Risk-Frameworks-and-Strategies.pptx

Wingate, U. (2006). Doing away with ‘study skills’. Teaching in Higher Education, 11(4), 457-469. doi: 10.1080/13562510600874268