Introduction and background

Contemporary ideas about health promotion have been developing through charters, declarations and research activity for over 40 years, starting with the Lalonde Report, 1974; the Alma Ata Declaration, 1978; the Ottawa Charter, 1986; the Jakarta Declaration, 1997; and the Bangkok Charter, 2005, as summarised by Signal and Ratima (2015). The Ottawa Charter introduced the idea of the settings-based approach, recognising that health is best facilitated through the communities in which people work, play, learn and love, across the life span (World Health Organisation [WHO], 1986).

Higher education is an important setting for health promotion for several reasons. 64% of tertiary enrolments in 2015 comprised of people aged 24 or younger (Education Counts, 2016). This is a time of life in which the brain is going through the final stages of developmental maturation, when many ways of thinking and being become well established (Dumontheil, 2016) and personal skills are developed, including knowledge of self-care, care for others, and for the environment. Students have also been found to be more likely to enrol and achieve in places of learning that demonstrate a commitment towards their health and wellbeing (Bradley & Greene, 2013). Positive effects on tertiary staff have also been reported from exposure to and involvement in health promotion activity, including increases in recruitment interest, role satisfaction and retention, as well as reductions in sickness absence (Bevan, 2010).

Higher education students and staff participate in learning, teaching and knowledge generation, all of which can include a focus on health, wellbeing and sustainability. Large numbers of staff and students are involved in higher education, and graduates are decision makers of the future. Consequently, health promotion in tertiary settings is potentially far reaching in its influence.

In 1996, the first International Conference of Healthy Universities was held in Lancaster, United Kingdom (UK), initiating the ‘Health Promoting Universities’ framework for action (Tsouros, Dowding, Thompson, & Dooris, 1998). This framework emphasised that healthy higher education should focus on three key elements: a healthy working and living environment (policies and culture); the integration of health promotion into the daily activities of the setting (teaching, learning and researching); and reaching out into the community (collaborating with stakeholders). These elements are as valid today as they were in 1998, and mature national higher education health promotion networks now exist in many countries, including the UK, Germany, Chile and Canada.

The Rio Declaration on Social Determinants of Health (WHO, 2011) reinforced the idea that health is not a simplistic matter of individual lifestyle choice, but also a result of environmental settings and social and policy factors. Social determinants of health were identified as those conditions in which people work, play, learn and love, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life. Determinants which have clear implications for students include the quality of housing (including halls of residence and rental housing); income and debt levels; access to healthcare and support, and the inequities that people experience in relation to these. Inequalities can be reduced and health determinants influenced by action at social, policy and environmental levels.

More recently, health promotion has been influenced by developments in the concepts of wellbeing, flourishing and positive psychology (Oades, Robinson, Green, & Spence, 2011). In Aotearoa New Zealand, the five ways to wellbeing (Mental Health Foundation, 2015), based on extensive research by the New Economics Foundation (2008), provide value to the health promotion toolkit. These ideas focus both on individual and community wellbeing, across all levels of social ecology (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). The five ways to wellbeing and positive psychology are focused on the idea of creating health, also known as salutogenesis (Lindstrom & Eriksson, 2006), rather than narrowly focusing on preventing ill health and tackling the causes and manifestations of pathogenesis. Organisational, public policy and community actions are also central approaches in working for the elimination of inequalities, and ensuring that optimum levels of health are achieved for all.

The Okanagan Charter (2015) synthesises earlier health promotion principles and concerns. This international charter for higher education health promotion was ratified following the contributions of 605 people from 45 countries. The Charter provides higher education settings with a useful structure to effectively respond to the evolving health challenges of the 21st Century.

In early 2016, the Tertiary Wellbeing Network Aotearoa New Zealand (TWANZ, 2016) was formally launched, following consultative work over the preceding three years. Australia also launched a Health Promoting Universities network in 2016, which has high level support from Vice Chancellors and Universities Australia. Both of these Australasian networks support and endorse the Okanagan Charter.

The next section provides an overview of the Okanagan Charter and its principles, making reference to core elements of some of the most commonly used models, approaches and tools relevant to the Aotearoa New Zealand context. This is followed by examples and suggestions applying the Charter’s action areas on campus.

The Okanagan Charter overview

The Okanagan Charter explicitly supports the WHO definitions of health and health promotion (WHO, 2006). Health is viewed as fundamentally holistic. Health promotion is seen as incorporating social and environmental interventions that include, but go beyond, a focus on the individual. The Charter is also explicit in its linkages with the Ottawa Charter, and usefully, a number of the Okanagan Charter’s action areas are very similar to those of the Ottawa Charter. A definition of wellbeing is not explicit, but reference to wellbeing is situated within the principle ‘build on strengths’, which is congruent with the ideas of positive psychology and increased happiness. In positive psychology, happiness is most powerfully generated through eudaimonic and hedonic sources working together. Hedonic sources of happiness include activities that bring about feelings of personal pleasure, enjoyment and satisfaction, whereas eudaimonic sources of happiness include activities that focus on social connectedness, development of potential, and optimal levels of functioning (Huta & Waterman, 2014).

The Okanagan Charter identifies higher education as having a unique and central role in society, in providing and generating transformational knowledge for the benefit of citizens and communities that can lead to the enhancement of health for the people who study, work and are collaboratively engaged with the activities and functions of higher education.

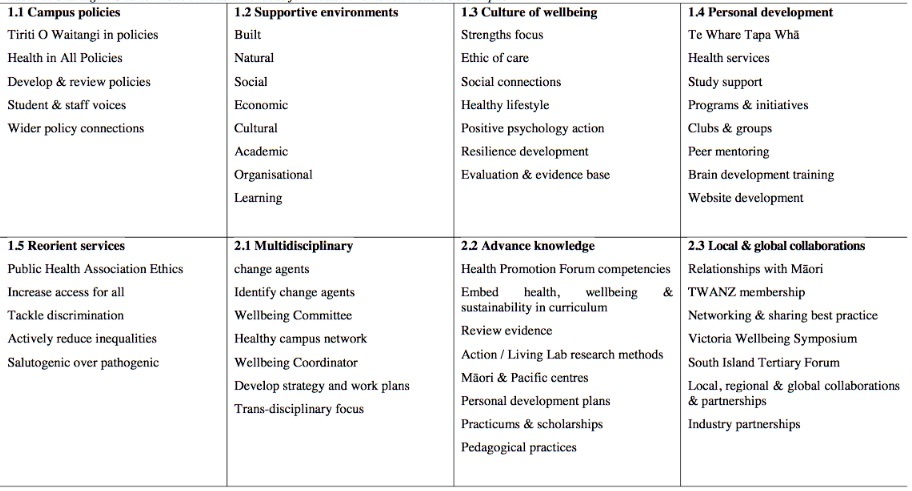

The Okanagan Charter has eight key principles for action, which underlie and apply to all of the Charter’s eight action areas. These action areas are interconnected with substantial areas of overlap, encouraging flexible and simultaneous use. Figure 1 shows a summary of the principles and action areas of the Okanagan Charter. Summary phrases have been used to distil the intent and core meaning of each principle and action area to assist practitioner and leadership thinking.

The eight action areas are spread across two Calls to Action. The first Call to Action has five action areas to ‘embed health into all aspects of campus culture, across the administration, operations and academic mandates’. These five action areas directly reflect the five action areas in the Ottawa Charter and are focused primarily on the operational delivery of day to day health promotion activity. The second Call to Action incorporates three action areas to ‘lead health promotion action and collaboration locally and globally’. These three action areas are more concerned with leadership, health promotion knowledge development and partnership building.

Applying the Okanagan Charter principles in Aotearoa New Zealand

The eight principles of the Charter are identified as guiding principles for mobilising systemic and whole of campus actions. The principles are designed to be used in multi-layered, flexible and localised ways.

a. Use settings and whole system approaches

The Okanagan Charter is focused on health promotion within higher education settings. In Aotearoa New Zealand, higher education is delivered from universities, polytechnics, institutes of technology and wānanga (Māori tertiary providers). A healthy settings approach is based on the principles of community participation, partnership, empowerment and equity (WHO, 1986). The Charter is similarly oriented, to contribute to conditions for health in tertiary settings and in wider society.

Relevant cultural models in Aotearoa New Zealand provide various means of increasing campus responsiveness to staff and students. A central model for understanding health is Te Whare Tapa Whā (Durie, 1985). Shaped like a whare or traditional Māori house, this model has strong foundations and four equal sides depicting tinana (physical health), hinengaro (emotional health), wairua (spiritual health) and whānau (social and family health). These dimensions of health need equal attention: The stronger each of these four walls is, the more likely the house of hauora, or health, will stand strong and experience wellness.

Te Pae Mahutonga (the Southern Cross star constellation) is the primary Māori model of health promotion in Aotearoa New Zealand (Durie, 1999). It is a model that follows a Māori kaupapa (themes), although, like Te Whare Tapa Whā, it can be used to work with peoples from all ethnicities. Six stars are shaped like the Southern Cross constellation, representing six areas of health promotion action. The two pointer stars are the prerequisites for health promotion action: Ngā Manukura (community leadership) and Te Mana Whakahaere (autonomy). In tertiary settings, these two stars can be applied to mean leadership and empowerment at all levels, including management support, peer educators, and change agents. Once these two pre-requisites are met, the other four key tasks of health promotion can be undertaken.

The four central stars of Te Pae Mahutonga represent the four central tasks of health promotion. Mauriora refers to cultural identity, including language, customs and the bonds shared with others. Waiora means the physical environment, including connection with, and action to protect the air, water, land and the biodiversity that sustains life. Toiora denotes healthy lifestyles, acknowledging that choices can be enabled or limited by the determinants of health. Te Oranga refers to participation in society, including equal access of individuals, groups and communities to life opportunities. Higher education institutions can support a Māori worldview by focusing on collective wellbeing, intergenerational connections, and through acknowledging the relationships between the physical and spiritual realms.

The Educultural Wheel is a teaching model promoting educational engagement for Māori (Hall, Hornby, & Macfarlane, 2015), which could be applied in tertiary settings to help facilitate cultural safety (Ramsden, 2002). The model has circular and interwoven concepts of whānaungatanga (interdependent relationships), manaakitanga (respect and care), rangatiratanga (leadership) and kotahitanga (solidarity). Te Ture Whakaruruhau, the Code of Ethical Principles for Public Health in Aotearoa New Zealand (Public Health Association, 2011) also provides useful guidance for working with others, particularly around the concepts of manaakitanga and whānaungatanga.

The Fonofale Model is a Pacific Island model of health, designed specifically for working with Pasifika in Aotearoa New Zealand (Pulotu-Endemann, 2001). Health is represented as a fale (house), held up by four pou (posts) that represent spiritual, physical, mental and other interactive aspects of health, sitting on the foundation of family, sheltered by the roof of cultural beliefs and values. The fale is surrounded by the influencing factors of time, context and environment, which link to settings and systems. Using the Fonofale Model in higher education settings will increase the effectiveness of health promotion with Pasifika.

b. Ensure comprehensive and campus-wide approaches

Tertiary campuses are complex settings. Staff are spread across many teams with differing roles; students study diverse programs in varied ways, and multiple campuses have differences in environmental configurations and resources. Tertiary organisations provide a range of health promotion actions. The challenge is to develop processes and systems that bring people together from diverse disciplines, departments and programs, to share resources and ways of working leading to health benefits for students and staff.

The population profile of Aotearoa New Zealand is changing rapidly (Statistics New Zealand, 2013) and it is forecast that student profiles in higher education will reflect these changing demographics. Māori and Pasifika populations are younger and growing more rapidly than the general population, which will influence future tertiary enrolments. Campus populations are also being influenced by a growth of Asian and other international students. Many Asian students hold values based on Confucianism (Ip, 2011), with a strong focus on collectivism rather than individualism; humanistic altruism and resource sharing; respect for teachers; and a duty to show benevolence and caring towards others. Health promotion practice in higher education needs to be responsive to these changing demographics in order to work effectively with Māori, Pasifika, Asian and other international students and staff.

c. Use participatory approaches and engage the voice of students and others

Actively seeking feedback and input from diverse groups of students and staff is critical for meaningful participation on campus. Participation needs to be vertical as well as horizontal; from the top down (including the Senior Leadership Team, Vice Chancellor or Chief Executive) as well as from the bottom up (with students and staff on campus). Seeking feedback from a diverse range of individuals and groups is central for increasing student and staff satisfaction and success. Participatory approaches need to include students and staff who are Māori, Pasifika, Asian, other internationals, refugees; those with additional challenges such as disabilities, young parents, LGBTI (lesbian, gay, takatāpui (intimate companion of the same sex*)*, bisexual, transgender and intersex); undergraduates and postgraduates; as well as staff from all faculties; research; teaching; management; administrative; health; recreation; and support areas.

Surveying students and staff regularly is a key means of engaging the voices of those on campus. Evaluation and surveying can be designed to achieve a greater response from diverse groups on campus whose input is sought.

d. Develop trans-disciplinary collaborations and cross-sector partnerships

Developing effective collaborations and partnerships strengthens health promotion action across diverse disciplines on campus. For example, nursing departments may add value in personal health factors, whereas psychology and social work could add value in mental health initiatives. Healthy eating or keeping active projects could be led by academic staff in nutrition and exercise science staff, and sustainability projects by environmental departments. Disciplines could collaborate in a range of ways to enhance synergies and results.

Strong relationships can help address social, economic, cultural and political determinants of health through partnerships outside the campus boundaries, such as with other higher education providers, iwi, local authorities, charities and industry. Developing partnerships through the national tertiary networks, such as TWANZ in Aotearoa New Zealand, or the Australian Health Promoting Universities Network are recommended. Alliances with the Public Health Association, the Health Promotion Forum, the Mental Health Foundation, the Ministries of Health, Social Development, Te Puni Kōkiri, the Ministry for Pacific Peoples and the Health Promotion Agency could all be beneficial.

e. Promote research, innovation and evidence-informed action

Higher education generates and disseminates knowledge and innovation. Curriculum and research in health, wellbeing and sustainability can play important roles in strengthening individual, group and community understandings and actions. Health promotion research, innovation and action can assist the development of skills and evidence-based approaches amongst tertiary staff and students.

Academic staff on Performance Based Research Funding (PBRF) contracts can be encouraged to engage with health promotion to develop academic outputs. Staff performance reviews, development plans and appraisals provide opportunities to discuss the development of health promotion projects and research.

Health promotion action within and beyond campus settings could be facilitated through use of planning and assessment tools. These include the Heath Equity Assessment Tool (Signal, Martin, Cram, & Robson, 2008), Health Impact Assessments (Haigh et al., 2015) and ‘RE-AIM’ (Hone, Jarden & Schofield, 2015). Logic models are useful in planning interventions and lend themselves well to evaluation. Evaluation types include process, impact and outcome evaluation (Victorian Government, 2008), and if health initiatives are shown to be successful, this evidence could be useful in maintaining support from senior leadership, or to secure support from funding bodies. This includes support of evidence-based kaupapa Māori health promotion and an expansion of the criteria around what constitutes sound scientific evidence.

f. Build on strengths

In recent times, there has been recognition that a focus on strengths, rather than deficits, can be more effective for salutogenesis, to increase resiliency as well as preventing ill health. Being strengths-based is also consistent with wellness centred approaches of Māori health, rather than an individualised deficit and disease focus.

A strengths-based approach connects with sector wide imperatives, such as the New Zealand Tertiary Education Strategy 2014-2019 (Ministry of Education (MoE), 2014), with its relevant strategic priorities: ‘Getting at risk young people into a career’ and ‘Boosting achievement of Māori and Pasifika’. The New Zealand Association of Positive Psychology has produced a useful workbook of strengths based research tools for measuring wellbeing, that could be used for baseline assessment and evaluating the impact of health promotion interventions (Jarden, 2011). The New Zealand Graduate Longitudinal Study (2016) is a recent initiative which incorporates a number of baseline measurement tools relating specifically to health and wellbeing, including self-esteem, self-efficacy and social support that could be used in local contexts.

Recent changes in health and safety law raise both opportunities and tensions for health promotion. Health is on the agenda for campus monitoring and reporting, and there is an opportunity to broaden the traditional focus on health and safety risk management outwards, to increase a focus on developing health and wellbeing. Those working in health promotion can develop alliances with those working in health and safety, to develop effective collaborations (Regional Public Health, 2012).

g. Value local and indigenous communities’ contexts and priorities

Health promotion in Aotearoa New Zealand acknowledges the rights and needs of Māori, as tangata whenua (indigenous people of the land) and partners in Te Tiriti o Waitangi (The Treaty of Waitangi). Te Tiriti o Waitangi is the constitutional founding document of Aotearoa New Zealand, between indigenous Māori and migrant Europeans. The underlying aspirations of health promotion are visible in Te Tiriti, which provides opportunities for Māori and non-Māori to enhance wellbeing and tackle inequality.

Health promotion in Aotearoa New Zealand needs to refer to Te Tiriti to help address the profound and persisting inequalities that Māori experience (Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand, 2002). Te Tiriti is based on principles of protection, partnership and participation. Under protection, inequalities need addressing and Māori kaupapa and tikanga (values) respected. Under partnership, manaakitanga is used to develop plans and establish relationships in good faith. Under participation, a genuine, long term commitment to whanaungatanga is required to make progress together. These principles are reflected in the Māori Education Strategy, Ka Hikitia (MoE, 2013), which states that tertiary education has an important role to play in sustaining and revitalising indigenous mātauranga (knowledge) and te reo (Māori language), benefiting wider society (Bialysok, Craik, & Luk, 2012).

Pasifika comprise of diverse ethnic groups in Aotearoa New Zealand who trace their origins to the island nations of the Pacific. Pasifika models of health promotion show strong similarities to Māori models, including an emphasis on collective wellbeing, the family, spiritualty, cultural identity, language and self-determination in improving health and wellbeing (Tu’itahi, S., & Lima, I. 2015). Pasifika have a special relationship with the New Zealand Government, which provides development and economic support. The Pasifika Education Plan (MoE, 2013a) aims to increase Pasifika learners’ participation, engagement and achievement including at a tertiary level.

h. Act on an existing universal responsibility

A concern with human rights, social justice, equity, dignity, respect for diversity and a universal right to health are embodied in this principle. The Bill of Rights Act 1990 and the Human Rights Act 1993 are of importance. The Bill of Rights Act applies to those undertaking public functions, including higher education staff, in that everyone has the right to freedom from discrimination, which is detailed in the Human Rights Act. These grounds include sex, sexuality, gender, ethnicity and disability. The Education Act 1989 points to the higher education role as the critic and conscience of society, which combined with human rights duties, forms a powerful mandate for tertiary education staff to tackle inequalities and promote social justice.

Te Ture Whakaruruhau, the Code of Ethical Principles for the Public Health Association (2011), provides useful practical guidance around planning and delivering health promotion for justice and equity. Ngā Kaiakatanga Hauora mō Aotearoa, the health promotion competencies for Aotearoa New Zealand also provides useful professional guidance for health promoters to improve health and health equity (Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand, 2012). These competencies comprise nine knowledge clusters, including advocacy, leadership and assessment, which can be used to enhance social justice.

Action Areas of the Okanagan Charter

The eight principles described above collectively underpin the eight action areas of the Okanagan Charter. Together they guide the development of health promoting higher education. The Okanagan Charter has two Calls to Action for higher education institutions. The first being to embed health into all aspects of campus culture, across the administration, operations and academic mandates, while the second is to lead health promotion locally and globally. Examples provided under the Charter action areas are drawn from the recent strengths-based evaluation survey into health and wellbeing initiatives from seven South Island tertiary institutions (Thorpe & Collie, 2016). Figure 2 also provides practical examples under each of the action areas, to consider when developing a healthier place of higher learning.

1.1 - Embed health in all campus policies

The Okanagan Charter views policies as mechanisms for organisational commitment to health, wellbeing and sustainability. Policies focus energies and areas of activity for development, implementation and change and as such can provide influential direction for health promotion action on campus. Aotearoa New Zealand stands in a unique position to support Māori achievement and wellbeing through obligations outlined in Te Tiriti o Waitangi, which need to be incorporated into higher education policies. Te Whare Tapa Whā and Te Pae Mahutonga could be used to develop and embed health in policies.

Health, wellbeing and sustainability outcomes need to visibly underpin campus policies. A campus-wide strategic approach includes health for all on campus. Policies should incorporate the diverse voices of students and staff on campus and reflect national priorities and strategies. They also need to incorporate short, medium and long term goals, and be allocated adequate human, financial and material resources. Policies must be regularly reviewed, updated and communicated, reflecting the changing student population over time.

1.2 - Create supportive campus environments

The Okanagan Charter identifies a wide range of campus environments to activate health promotion: built, natural, social, economic, cultural, academic, organisational and learning environments. Campus environments can be reviewed as to their effectiveness in supporting health, wellbeing and sustainability.

The built environment can be designed to enhance interpersonal safety and access, and promote physical activity. This could include incorporating sustainability and universal design principles on campus development projects, engaging students in capital works programs, and providing disabled access and accommodation. Natural environments support sustainable practices, such as working towards a low carbon energy scheme on campus, developing community gardens, and waste reduction. Supportive social environments can include pastoral care for diverse student groups, student advocacy, and wellbeing spaces. Supportive economic environments can include zero fees schemes for students, scholarships and emergency fund provision. Supportive cultural environments influence how welcome and engaged people feel on campus, such as bicultural competency building, bilingual childcare, Confucius centres (promoting Chinese language and culture), multi-lingual staff, and the rainbow tick (awarded to organisations completing sexual and gender diversity certification). Supportive organisational environments can include diverse learning needs, staff development and supervision, and fair trade accreditation. Lastly, supportive academic and learning environments can include student representatives on programs, reviews of demanding courses and barrier free trust audits.

1.3 - Generate thriving communities and a culture of wellbeing

‘Building a flourishing campus involves the development of a safe and supportive environment, building a sense of community, increasing social inclusion and participation, and increasing awareness of emotional health and wellbeing issues’ (Thorpe & Collie, 2016: 16). Flourishing campuses also celebrate cultural identity and diversity, promote mental health and wellbeing, facilitate social connections, promote healthy lifestyles and generate a sense of belonging.

A strengths-based approach helps develop a flourishing culture of wellbeing and increased resilience on campus, where individuals and groups feel welcome and engaged in decision making. An ethic of care can be fostered by providing comprehensive training, such as mental health first aid to staff, including lecturers and residential advisors, and through providing spaces and support for Māori, Pasifika, mature students and those from diverse faiths on campus, and through volunteering opportunities. As in other action areas, baselines and evaluation measures can also help establish development needs and track gains made.

1.4 - Support personal development

Health promotion on campus supports personal and social development through enhancing life skills, providing information, and education for health, which could use Te Whare Tapa Whā as a foundation. This increases the focus on health literacy, opportunities to exercise more control over personal health and environments, and supports healthy choices. Many larger tertiary campuses in Aotearoa New Zealand have student health centres offering subsidised health care, counselling, early intervention, and screening services. Specific teams, positions and programs are commonly dedicated to supporting and improving outcomes for priority student groups, including Māori, Pasifika, international students, and those with disabilities.

Campus support of personal development can be wide ranging, including professional opportunities for staff; support for differing learning needs and disabilities; training of staff, mentors and residential advisors; wellbeing workshops; subsidised gym membership; clubs; mentorship; and peer support programs. Given many tertiary students are aged under 25 years, staff knowledge of basic brain development and brain plasticity would be helpful. Campus websites and wider social media play an essential role in connecting students and staff to available services, programs and events, including those from relevant community providers.

1.5 - Create or re-orient campus services

Health and wellbeing services on campus must be designed and delivered in such a way as to encourage uptake and overcome barriers to access. ‘Access to services can be a major barrier to student success and considerable effort should be invested in the identification and removal of barriers to make campus services and programs responsive’ (Thorpe & Collie, 2016). Groups that experience the greatest inequalities should be given the greatest priority. Many campuses in Aotearoa New Zealand offer tailored services for priority groups, such as those first in their families to enrol in higher education and LGBTI students. Increased use of te reo, wellness checks, and early intervention and technology support for those experiencing learning difficulties, are examples of reorienting services to support priority student success. Developing a range of support mechanisms in higher education is important for attracting and retaining Māori staff and students.

A focus on reorienting services to be responsive to those with the greatest needs is in line with the Public Health Association Code of Ethical Principles for Public Health. A wide range of student voice mechanisms can be used to represent student feedback and input into services, programs and events. Incorporating diverse student voices into decision making aids the reduction of inequalities, and is consistent with a salutogenic approach, focused on growing health and wellness.

2.1 - Integrate health, wellbeing and sustainability in multiple disciplines to develop change agents

This action area focuses on the development of leadership roles to drive change and integrate health, wellbeing and sustainability across higher education disciplines and the curriculum. The identification of change agents and leaders on campus can positively influence healthy outcomes, enabling health promotion activity through individual roles, and formal or informal collaborations.

There are some useful mechanisms for developing strategy, work plans and action on campus (Healthy Universities, 2009). Much of the operational planning can effectively be undertaken by a health promotion steering committee, supported by a wider health promotion network. Bottom up energies and top down resources can form a strong partnership to represent and address the needs and priorities of students and staff. A health promotion or wellbeing coordinator can play a central role on campus to ensure that communication is effective, voices are heard, strategy remains relevant, action is taking place and outcomes are beneficial. This role needs to have recognised seniority within the organisation, to help facilitate health promotion engagement with the diversity of internal and external stakeholders and partners involved.

Challenges may be experienced when establishing wellbeing committees, networks and health promotion coordination roles, around concerns such as where they sit within the organisation, accepted understandings of roles, and financial investment. A business case is likely to be needed, as well as terms of reference and a strategic plan.

2.2 - Advance research, teaching and training for health promotion knowledge and action

The role of higher education in research includes knowledge generation, learning and teaching. Opportunities exist to embed health, wellbeing and sustainability into the curriculum. Curriculum and research into health, wellbeing and sustainability provide opportunities to develop health promotion knowledge production and skills. Positive pedagogical practices can be emotionally protective for students, enhancing health (Oades, Robinson, Green, & Spence, 2011).

Examples of advancing research, teaching and training for health promotion knowledge and action include Māori and Pasifika centres on campus, adopting action research or a living lab approaches, providing practicums and scholarships for health promotion projects, and promoting sustainable values, practices and behaviours on campus. Making use of the Health Promotion Forum Competencies and completing formal qualifications in health promotion could also contribute to this. Some activities could also be connected to PBRF requirements or personal development plans.

2.3 - Lead and partner towards local and global action for health (Collaboration)

Higher education institutions in Aotearoa New Zealand are well-placed to lead local and global action for positive change in health, wellbeing and sustainability. Relationships and collaborations with external stakeholders, such as iwi, industry and the community, can help drive change both on campus and in the wider community.

There is a range of local or regional networks or collaborative groups in Aotearoa New Zealand. TWANZ offers networking opportunities, case studies and a wide range of resources relevant to healthy tertiary settings. The South Island Tertiary Forum connected with TWANZ focuses on health and wellbeing issues, research and practice initiatives in the South Island. The Victoria Wellbeing Symposium provides an opportunity for knowledge sharing nationally. Looking ahead, Universities New Zealand could be engaged more directly with health promotion issues, as could NZQA or Ako Aotearoa.

Tertiary partnerships can be fostered with other external partners, such as the Society for Youth Health Professionals, Ara Taiohi, Alcohol Action, or Fizz. International networks support global action for health, such as Healthy Universities UK (which has affiliate members from outside of the UK), the International Wellbeing in Higher Education Network, and the International Positive Education Network. Joining such networks can provide direction and support for health promotion vision and action, on and beyond campus.

Conclusion

The international Okanagan Charter builds on influential health promotion charters in higher education settings. The Charter’s principles and calls to action make a valuable contribution to health promotion practice in higher education. The Charter is highly applicable and relevant to national tertiary needs and approaches, particularly with its focus on valuing indigenous communities and priorities.

The development of the Okanagan Charter has usefully coincided with the emergence of TWANZ and the Australian Health Promoting Universities Network, at a time when much health, wellbeing and sustainability activity is being generated. The Okanagan Charter is viewed as a useful and flexible framework to further develop strategic planning, coordination and integration in tertiary settings.

This paper is an early effort to develop understandings of its meaning and practice in the context of Aotearoa New Zealand. Institutions of higher education are encouraged to work with the Okanagan Charter and its Calls to Action, to embed health across campuses and lead health promotion action and collaborations locally and globally.

The authors may be contacted via:

Craig Waterworth

c.waterworth@massey.ac.nz

References

Bevan, S. (2010). The business case for employees’ health and wellbeing. Retrieved from http://www.theworkfoundation.com/downloadpublication/report/245_245_iip270410.pdf

Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I., & Luk, G. (2012). Review: Bilingualism: Consequences for mind and brain. Trends In Cognitive Sciences 16(4), 240-250.

Bradley, B. J., & Greene, A. C. (2013). Do health and education agencies in the United States share responsibility for academic achievement and health? A review of 25 years of evidence about the relationship of adolescents’ academic achievement and health behaviors. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 52(5), 523-532.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P.A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R.M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology. (pp. 793–828). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Dumontheil, I. (2016). Adolescent brain development. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 1039-44. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.04.012

Durie, M. (1999). Te Pae Mahutonga: A model for Māori health promotion. Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand Newsletter, 49.

Durie, M.H. (1985). A Māori perspective of health. Social Science Medicine, 20(5), 483-486.

Education Counts. (2016). Provider based enrolments. Retrieved from https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/tertiary-education/participation

Graduate Longitudinal Study New Zealand. (2016). First follow-up descriptive report graduate longitudinal study New Zealand. Retrieved from https://www.glsnz.org.nz/files/1468361988403.pdf

Haigh, F., Harris, E., Harris-Roxas, B., Baum, F., Dannenberg, A. L., Harris, M. F., & … Ng Chok, H. (2015). What makes health impact assessments successful? Factors contributing to effectiveness in Australia and New Zealand. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1-12. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-2319-8

Hall, N., Hornby, G., & Macfarlane, S. (2015). Enabling School Engagement for Māori Families in New Zealand. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 24(10), 3038. doi:10.1007/s10826-014-0107-1

Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand. (2002). TUHA–NZ: A Treaty understanding of hauora in Aotearoa New Zealand. Retrieved from http://www.hpforum.org.nz/resources/Tuhanzpdf.pdf

Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand. (2012). Ngā Kaiakatanga Hauora mō Aotearoa - The Health Promotion Competencies for Aotearoa, New Zealand. Retrieved from http://www.hauora.co.nz/assets/files/Health Promotion Competencies Final.pdf

Healthy Universities, (2009). Getting started. Retrieved from http://www.healthyuniversities.ac.uk/getting- started.php?s=203&subs=51.

Hone, L., Jarden, A., & Schofield, G. (2015). An evaluation of positive psychology intervention effectiveness trials using the re-aim framework: A practice-friendly review. Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(4), 303-322. doi:10.1080/17439760.2014.965267

Huta, V., & Waterman, A. (2014). Eudaimonia and Its Distinction from Hedonia: Developing a classification and terminology for understanding conceptual and operational definitions. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(6), 1425-1456.

Ip, P. (2011). Concepts of Chinese folk happiness. Social Indicators Research, 104(3), 459. doi:10.1007/s11205-010-9756-7.

Jarden, A. (2011). Positive Psychological Assessment: A practical introduction to empirically validated research tools for measuring wellbeing. Retrieved from http://www.positivepsychology.org.nz/uploads/3/8/0/4/3804146/workshop_4_-dr_aaron_jarden positive_psychological_assessment_workbook.pdf.

Lindstrom, B., & Eriksson, M. (2006). Contextualizing salutogenesis and Antonovsky in public health development. Health Promotion International, 21(3), 238-244.

Mental Health Foundation. (2015). Five Ways to Wellbeing: A best practice guide. Retrieved from https://www.mentalhealth.org.nz/assets/Five-Ways-downloads/mentalhealth-5waysBP-web-single- 2015.pdf

Ministry of Education. (2013a). Pasifika Education Plan 2013 -2017 Retrieved from http://www.education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Ministry/Strategies-and- policies/PasifikaEdPlan2013To2017V2.pdf.

Ministry of Education. (2013). The Māori Education Strategy: Ka Hikitia - Accelerating Success 2013 -2017.

Ministry of Education. (2014). Tertiary Education Strategy. Retrieved from http://www.education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Further-education/Tertiary-Education-Strategy.pdf.

New Economics Foundation. (2008). Five Ways to Wellbeing: The evidence. Retrieved from http://www.neweconomics.org/publications/entry/five-ways-to-well-being-the-evidence.

Oades, L.G., Robinson, P., Green, S. & Spence, G.B. (2011). Towards a positive university. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(6), 432-439.

Okanagan Charter: An international charter for health promoting universities and colleges. (2015). Retrieved from http://internationalhealthycampuses2015.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2016/01/Okanagan-Charter- January13v2.pdf.

Public Health Association. (2011). Te Ture Whakaruruhau: Code Of ethical principles for public health in Aotearoa New Zealand. Retrieved from http://www.pha.org.nz/documents/120305code-doc.pdf.

Pulotu-Endemann, K. (2001). Fonofale model of health. Retrieved from http://www.hauora.co.nz/resources/Fonofalemodelexplanation.pdf.

Ramsden, I. (2002). Cultural safety and nursing education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu. (Doctoral dissertation. Victoria University of Wellington, Aotearoa/New Zealand). Retrieved from http://www.researchgate.net/publication/33688653.

Regional Public Health. (2012). A guide to promoting health and wellness in the workplace. Wellington: Regional Public Health.

Retrieved from http://www.education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Ministry/Strategies-and-policies/Ka-Hikitia/KaHikitiaAcceleratingSuccessEnglish.pdf.

Signal, L., Martin, J., Cram, F., & Robson, B. (2008). The Health Equity Assessment Tool: A user’s guide. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

Signal, L., Ratima, M., & Raeburn, J. (2015). The origins of health promotion. In L. Signal, M. Ratima (Eds.), Promoting health in Aotearoa New Zealand. (pp. 19-41). Wellington, New Zealand: Otago University Press.

Statistics New Zealand. (2013) 2013. Census quickstats about national highlights. Retrieved from http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/profile-and-summary-reports/quickstats-about-national- highlights/cultural-diversity.aspx.

Thorpe, A., & Collie, C. (2016). South Island tertiary health and wellbeing survey: General report. Retrieved from http://www.cph.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/SITertiaryHealthWellbeingSurvey.pdf.

Tsouros, A.D., Dowding, G., Thompson, J., & Dooris, M. (1998) Health promoting universities. Retrieved from http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/101640/E60163.pdf.

Tu’itahi, S., & Lima, I. (2015). Pacific health promotion. In L. Signal, M. Ratima (Eds.), Promoting health in Aotearoa New Zealand. (pp. 64-81). Wellington, New Zealand: Otago University Press. TWANZ (Tertiary Wellbeing Aotearoa New Zealand). (2016). Retrieved from http://www.twanz.ac.nz/.

Victorian Government. (2008). Measuring health promotion impacts: A guide to impact evaluation in integrated health promotion. Retrieved from http://betterevaluation.org/resources/guide/measuring_health_promotion_impacts. Walton, M., Tu’itahi, S., Stairmand, J., & Neely, E. (2015). Settings-based health promotion. In L. Signal, M. Ratima (Eds.), Promoting health in Aotearoa New Zealand. (pp. 241-263). Wellington, New Zealand: Otago University Press.

WHO. (1986). The Ottawa charter. Retrieved from http://www.hauora.co.nz/assets/files/Global/Ottawa Charter 1986.pdf

WHO. (2006). The WHO health promotion glossary. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/about/HPG/en/.

WHO. (2011). Rio political declaration on social determinants of health. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/sdhconference/declaration/Rio_political_declaration.pdf.